When I was in high school, I got an A in every subject I ever took. I didn’t find out until later that I hadn’t learned as much as I thought. But man, I knew how to make A’s!

My dad was in the military, so I knew all about West Point. For years I wanted to go to college there and become an Army officer. The problem is, you have to get an appointment, and many of these decisions are made by politicians. Because we moved around a lot, I didn’t grow up in any single state and I didn’t know any senators, congressmen or governors.

I applied for an appointment from Kansas, my dad’s home state. The governor was a busy man and he asked his staff to study the applications and recommend a choice. I guess my resume was pretty strong because I was one of those selected, even though I had never lived in Kansas.

Talk about luck! I was thrilled. My boyhood dream had come true.

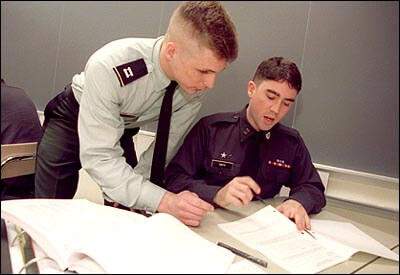

After I got there, I didn’t feel so lucky. Yes, the experience was pretty much what I had imagined it would be, but much more. All classes were mandatory—over 20 credit hours per semester. I even attended classes on Saturday. I found out there were a lot of guys my age who were smarter than I was. It was humbling. I wasn’t used to that feeling, and I didn’t like it. It motivated me to work as hard as I could, in spite of the pressures, which were many.

There was a lot more to being a cadet than attending class. There was a rule book two inches thick, and I served many weekend “punishment tours” for my failures to comply. Upperclassmen were not allowed to befriend freshmen or call them by their first name. On the other hand, they were allowed to harass us.

On Sunday, attendance at Protestant, Catholic or Jewish chapel was mandatory. We marched in formation to services. We also marched in parades twice a week. I came to hate parades and martial music. We weren’t allowed to leave the West Point campus, even on weekends. Back then, freshmen weren’t even allowed to go home for Christmas.

Participation in a varsity or intramural sport was required every semester. Instead of three months of vacation, most of the summer involved military training. This “system” was designed to put a ton of pressure on cadets and weed out those who couldn’t handle it. More than a hundred of my classmates left or were forced out during my freshman year.

By the time I was a senior I had become a better student, and my GPA was in the top 5% of my class. I was proud and happy to graduate and began my career as an Army officer.

Still, I always thought of my time at West Point as a mixed bag. I’ve returned to visit the place several times since then, and there have been some positive changes. But I always felt uneasy and was glad to leave.

Now that I’ve learned that adolescence is a one-time-only chance to lay down the foundation for a superior mind, I realize that I got lucky in another way by attending West Point.

In high school I was able to make good grades without thinking seriously about what I was learning, and I had no mentors who made me think. My real passions were writing poetry and playing golf. I played 18 holes of golf every day, weather permitting. As I recall those years, I realize I did very little to construct a foundation for critical thinking and judgment.

My courses at West Point changed that. They were challenging and sometimes interesting, even though I used very little of what I learned in my career. On the other hand, the courses made me think. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was trying like crazy to exercise my prefrontal cortex – the part of the brain involved in critical thinking and judgment – in practically every course: civil engineering, fluid mechanics, strength of materials, quantum physics, and nuclear engineering required a lot of thought and problem solving. Math courses involved studying a procedure at night and the next day solving three problems on a blackboard without referring to the text. At random, one of us would be called on to explain his work in front of the others – for a grade. Military history was all about analyzing why battles were won and lost. Even English classes forced me not just to read literature, but to understand it.

Yes, the experience was arduous, but my time at West Point was one of the luckiest things that ever happened to me. By doing the work I constructed a massive foundation for critical thinking, judgment, and problem-solving. Today, I use this foundation to connect the dots about learning and development.

Yes, the experience was arduous, but my time at West Point was one of the luckiest things that ever happened to me. By doing the work I constructed a massive foundation for critical thinking, judgment, and problem-solving. Today, I use this foundation to connect the dots about learning and development.

So – Thank you, West Point. Of course, going to a school like that isn’t the only way to build a foundation for critical thinking, but it worked for me. It was tough medicine, and it did the job. And when it was over, so was my adolescence.

Helping your child develop vital thinking skills is perhaps the best way to prepare them for leaving the nest. My new book: How Your Teen Can Grow a Smarter Brain.

Helping your child develop vital thinking skills is perhaps the best way to prepare them for leaving the nest. My new book: How Your Teen Can Grow a Smarter Brain.

You can grow the bond with your child through better listening. Download the FREE ebook, Listening to Understand.